How to make a Board Game: Step 1 — Storytelling

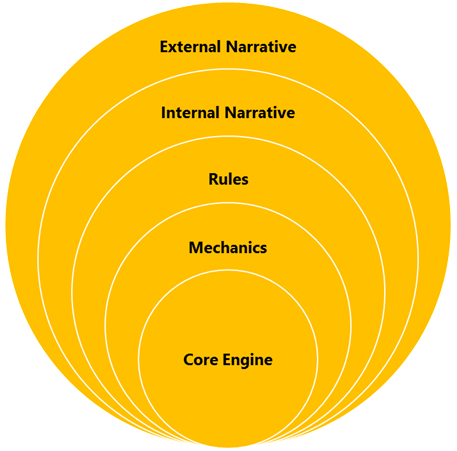

Checkers is a game that tells a tale. Smallworld is a game that has a narrative feel of the rise and fall of empires. The game of life, is well, life. These stories are told through five various levels of communication, either intentional or by chance.

This is why, when I make games, I try to provoke a specific emotion.

Engine (Core)

What’s left once you remove all the mechanics that place impediments in your players’ way? Obviously, this isn’t a really excellent or deep game, but there is still a goal to achieve. The core engine is the absolute minimum of mechanics required to make a game work.

Mechanics

Games aren’t really excellent unless they feature limits that make it difficult for players to complete the goal. Mechanics should include impediments, whether they are created by the game itself or by other players. Player elimination and hand management are examples of mechanics. They are sometimes purposefully created, and other times they are the result of regulations.

Rules

Only moving a checkers piece in a diagonal direction. Gaining certain gold for taking a space. These are the rules that govern how mechanics is applied. The border between rule and mechanism is rather blurry, and people will dispute over it. A mechanism is the game’s premise, and a rule is the way it’s handled to maintain balance.

Internal Storytelling

The basic engine, mechanics, and rules — which make up the gameplay — aren’t the only ways the game communicates with players. The game’s subject, plot, imagery, components, and even box design all communicate to players. Except for the gameplay, the internal story includes everything about the game as a whole.

External Storytelling

There’s more to games than what’s on the box. They are also the marketing that was employed to promote them — the advertisements and actions of the game makers. They’re the Kickstarter campaign and the retail outlets where they’re sold. Games are the people who discuss them on message boards and play them at conferences. People argue that games are all they promise to be.

Conclusion

Every level of communication has an impact on how people view your game. If the game’s underlying engine or mechanisms are flawed, the game will suffer as a result. People will be too hesitant to begin if you muck up the rules, they will play improperly, they will give you bad reviews online, or a mixture of all three. If you muck up the internal story, you’ll be losing out on a lot of possibilities to make your game more intelligible, which means it’ll be poor or unclear. You might end up in obscurity, create a terrible community, or never get the input you really have to survive if you botch up the external story.

You want people to have a good time, interact, and communicate with one another. You want everyone to get away from their problems for a time and do something else. Poor communication, at any level, is a barrier to eliciting the desired emotions in your game. It’s more often than not, that good communication is felt rather than spoken or even seen.

Till the next time.